Perspectives on the History of Tarot

发布时间:2025-06-26 15:14:04 人气: 作者:Simon Wintle

From a Renaissance Card Game to a Medium of Spiritual Meaning and Identity.

Italy is generally regarded as the birthplace of tarot, along with Italian-suited playing cards, which explains why most tarot decks still retain Italian suit symbols. According to playing-card historians, tarot was originally a card game invented in the fifteenth century, whose principal innovation was the introduction of a permanent set of trump cards into an otherwise standard playing-card deck. Helen Farley (2009) suggests that Duke Filippo Maria Visconti of Milan is “the most likely candidate for the inventor of that first deck,” sometime in the early fifteenth century. Tarot therefore began as an augmented pack of early Italian playing cards - seventy-eight cards rather than the usual fifty-two - emerging from a specific cultural milieu: late-medieval southern Europe.

From this historical starting point, tarot can be approached from several complementary perspectives. The most straightforward, exoteric explanation understands tarot simply as a game, developed within a Christian society whose imagery naturally reflects the religious and moral worldview of its time. The Church dominated public life, and many early tarot images draw upon familiar Christian themes, allegories, and moral exempla.

Alongside this public, orthodox culture, however, there existed more private intellectual currents. Courts such as that of the Duke of Milan fostered interests in astrology, alchemy, classical philosophy, and other bodies of knowledge inherited from antiquity and the medieval world. It is within this context that tarot has often been interpreted as possessing an esoteric dimension, appealing to those whose interests extend beyond the game itself. Over the centuries, tarot has repeatedly been aligned with various philosophical, hermetic, and occult traditions, many of which continue to be studied and practised today.

A third perspective approaches tarot primarily as a visual and artistic form. Many decks have been created with considerable aesthetic ambition, and their imagery can be appreciated independently of any gaming or esoteric function. Regardless of symbolic interpretation, tarot has provided a flexible format through which artists have generated new imagery, styles, and visual narratives across different periods.

In the earliest surviving tarot decks, both the order of the trump cards and their iconography vary considerably, reflecting a worldview in transition during the Renaissance. Tarot had not yet crystallised into a fixed symbolic system; its imagery responded to local cultural contexts and prevailing ideas about the structure of the cosmos. Had the game emerged in a different civilisation, it would inevitably have drawn upon a different symbolic vocabulary. The trump figures were understood as analogies of universal principles, expressing contemporary notions of humanity’s place within the cosmic and divine order. Their imagery often carried an instructive or moralising function, aligned with the philosophical and spiritual concerns of an educated elite. In this sense, early tarot functioned not merely as a game, but as a form of cultural expression—an implicit statement of identity and worldview.

Above: the Visconti-Sforza Tarocchi, c.1460, produced for wealthy and status-conscious elites, outwardly pious... more →

Although tarot was not widely used for divination until the eighteenth century, elements of Christianised pagan imagery appear in some earlier tarocchi decks. In certain cases, these images may carry implicit critiques of ecclesiastical authority or reflect intellectual currents that circulated beyond official doctrine. Some decks exhibit intriguing combinations of Christian symbolism with hermetic, Neoplatonic, or classical ideas, suggesting symbolic programmes that echo Christian eschatology while subtly reframing it through alternative metaphysical perspectives. Such imagery need not imply a coherent occult system, but it does point to tarot’s capacity to serve as a vehicle for layered meaning within educated and semi-private cultural circles.

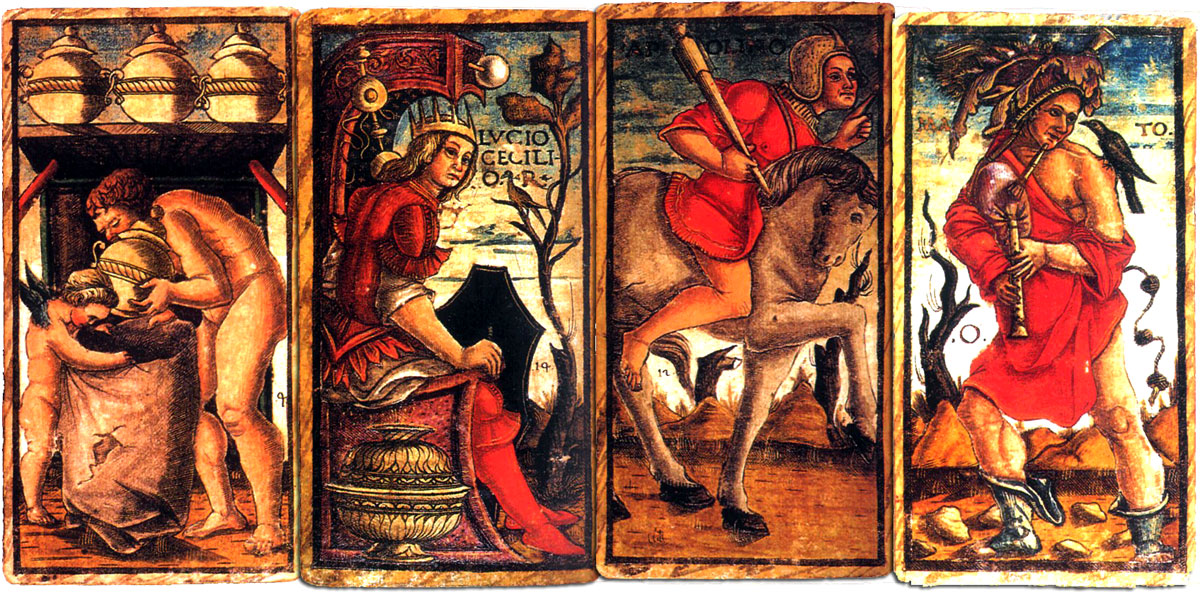

Above: the 4 “Guildhall Library Tarocchi Cards” from the Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing Cards collection of historic playing cards, believed to have been painted during the 15th century. These are hand-painted and gilded by an illuminator, reckoned to be two pairs of cards from two different decks owing to differences in their size. The Guildhall catalogue records both pairs as having been found in an old chest in Seville (Spain) suggesting the possibility of Sephardim Jewish or other mystical influences. The Page of Batons has a Spanish-type club and is not holding his suit symbol as is common in all known Italian cards. He is depicted in a hunting scene, perhaps denoting moral strength and virility. The cards have no titles or numerals, so their sequence or hierarchy was presumably familiar to the players. The World card shows the New Jerusalem cantered on the rebuilt Holy Temple. The black and white chequered floor tiles on the ace of cups suggest the dualistic nature of the material realm upon which the spiritual life is rebuilt through practising higher moral virtues. The ace of swords (or Sun) suggests the idea that the endless cycles of birth and rebirth can be penetrated by spiritual wisdom. And we can also observe that the suit symbols were batons, cups, swords… and probably coins… [Images by kind permission of the Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing Cards Collection and the London Metropolitan Archives, City of London Corporation].

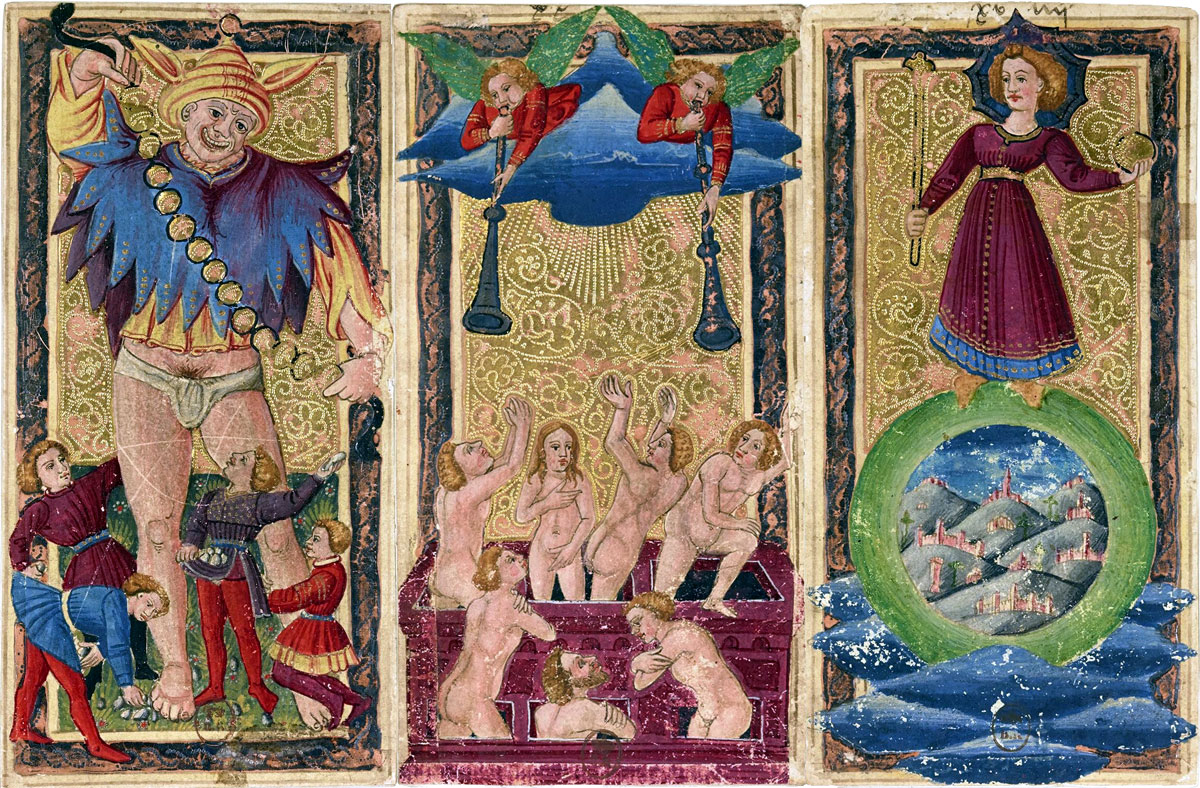

Above: an interesting mix of intelletual influences can be seen in this late 15th century hand-painted tarot from Italy. The Last Judgement mirrors Christian eschatology but also hermetic rebirth more →

From its earliest manifestations, tarot possessed the potential to function as more than a simple card game. Its imagery could be adapted to express philosophical concerns, moral ideals, and forms of social or intellectual identity, particularly within educated and elite circles. In this respect, tarot offered a flexible symbolic language through which worldview and self-understanding might be articulated.

The Sola-Busca tarot represents an especially concentrated example of this potential. While it has often been interpreted as an alchemical or initiatory guide, the deck does not present a systematic esoteric programme. Rather, it draws selectively upon alchemical, classical, and moral imagery familiar within late-fifteenth-century humanist culture, inviting informed interpretation without prescribing a fixed path of initiation. Its symbolism appears less as a manual for secret practice than as an expression of learned identity and moral imagination within a restricted cultural milieu. more →

Above: four cards from the Sola-Busca Tarocchi, Ferrara, 1491 more →

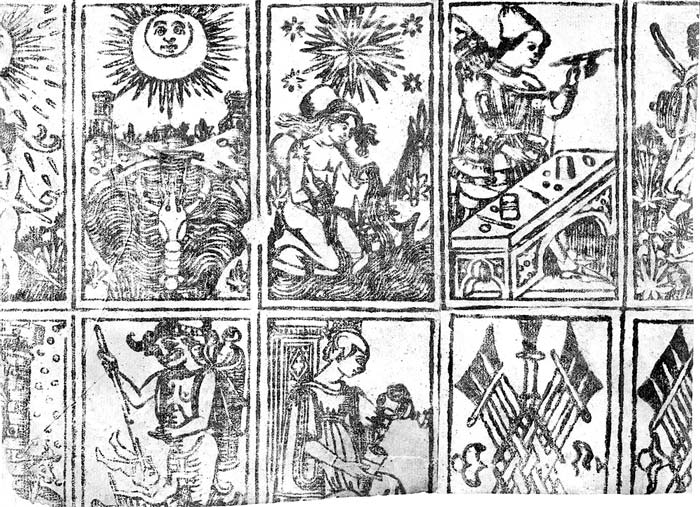

Above: detail from the Cary Collection uncut and uncoloured sheet of tarot cards (housed in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut) probably printed in Milan and possibly dating as early as c.1500. The entire sheet is available for digital download here. The images are untitled and unnumbered, suggesting that players may have already known the sequence or hierarchy of trump cards in play from contemporary knowledge. Much of the imagery is recognisable as anticipating the more familiar Tarot de Marseille designs (see below) whilst other features are common to other early Italian decks such as the Visconti-Sforza and D'Este decks. Thus it looks like a prototype or intermediate form of the Tarot de Marseille design.

Tarot de Marseille

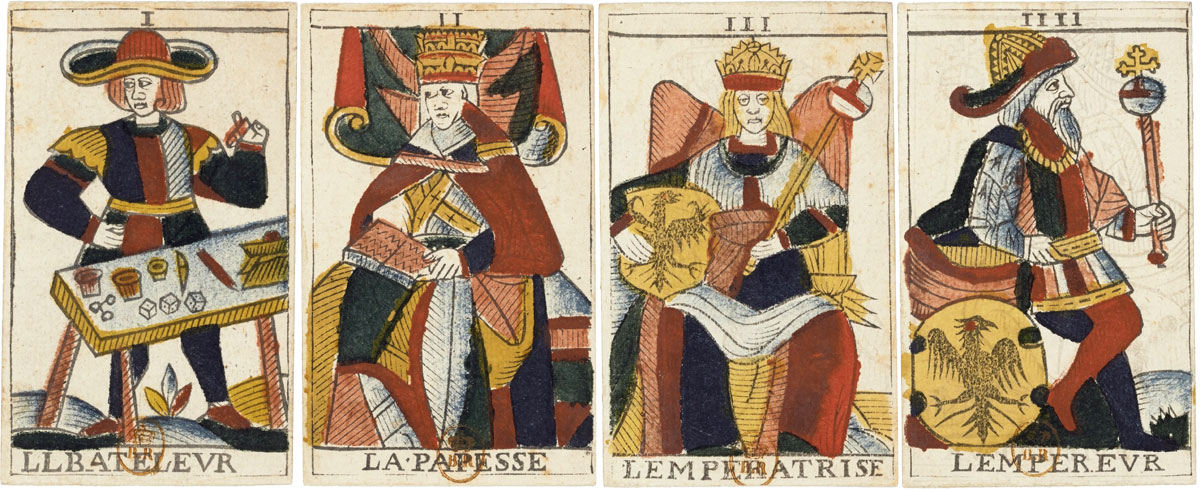

The game spread in Europe from Ferrara, Bologna and Milan towards Germany, Switzerland and France, where the Swiss Tarot and Tarot de Marseille were eventually born. The French word ‘tarot’ derives from the Italian ‘tarocco’. The Tarot de Marseille derives from the Milanese style of tarot, with the names of the court cards and trumps added at the bottom. It first began appearing in the mid 1600s. Speaking of the Tarot de Marseille, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Marianne Costa (2009) see the tarot as sacred art, like a Mandala (Yantra in Hinduism), in which all the individual symbols are part of the whole. Its meanings gradually reveal themselves to us, intuitively.

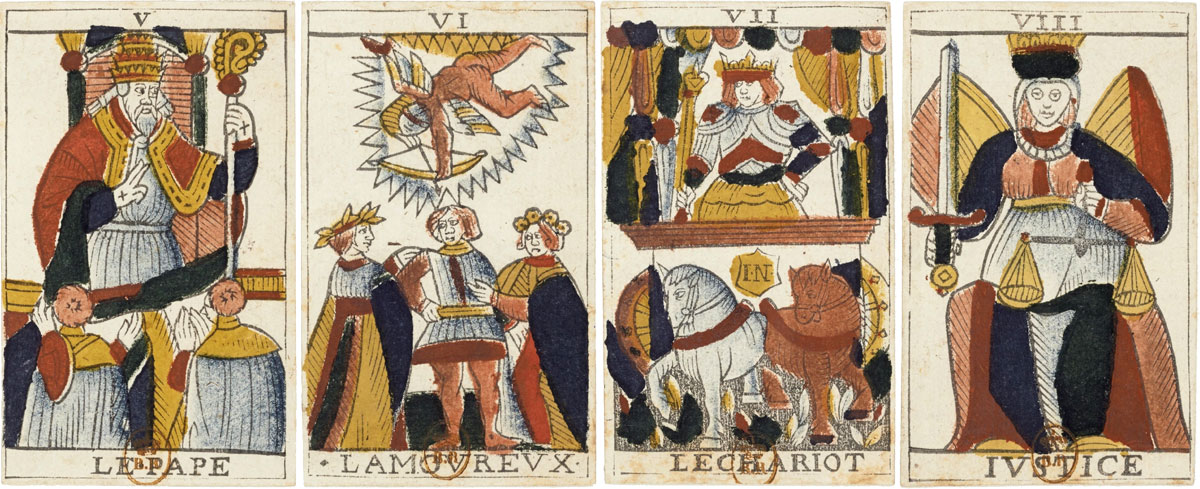

Above: the earliest known ‘Tarot de Marseille’ deck produced by Jean Noblet, Paris, c.1650.

Above: Tarot de Marseille by Jean-Baptiste Madenié, Dijon, early 18th century. The page of cups holds his cup upwards, open to above, whilst the Magician also holds his wand aloft and the queen her sword. They all glance downwards. The trump cards are named and have Roman numerals to designate their value during play. Images courtesy Frederic C. Detwiller.

Animal and Mythological Tarots

By the mid 18th century Tarot packs with French suit signs were being produced in France, Austria, Switzerland and Germany with trumps displaying exotic animals, popular imagery, dancing, folklore, historical scenes - see examples. These were for playing the game of Tarock (not cartomancy or divination).

Egyptian Tarot

1750-1800: the occult and divinatory origin of Tarot - Antoine Court de Gébelin (1725-1784)

D

uring the late eighteenth century, the Tarot was imbued with an air of mystery by Antoine Court de Gébelin in Volume VIII of his encyclopedic work Le Monde Primitif (1781). He proposed a theory linking the cards to ancient Egypt, suggesting they held philosophical and divinatory secrets. This gave the Tarot an exotic, esoteric allure, though his claims were speculative rather than historically grounded.

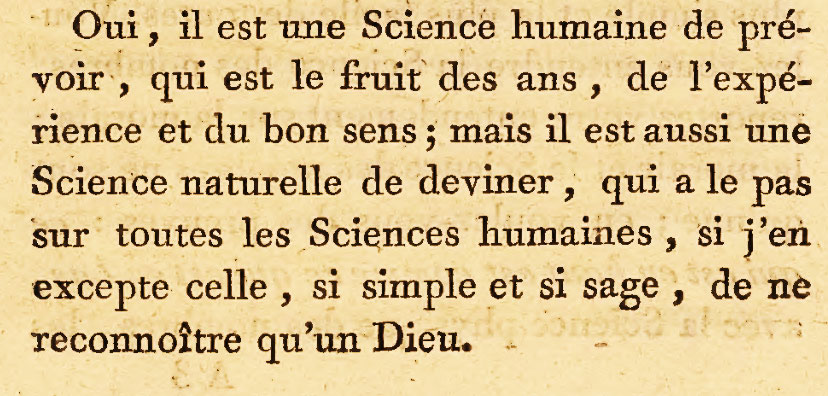

Above: excerpt from Court de Gébelin's treatise Monde Primitif (volume 8, p.366, 1781), in which an exotic Egyptian origin is proposed for the allegorical images in the Tarot deck. At the end is a comparison with the invention of chess in India (6th century). Source: Internet Archive Monde Primitif vol.8

Later mystics expanded on these myths, weaving the Tarot into a grand narrative of "secret wisdom" and occult tradition. The so-called Egyptian Tarot became a Western confection, part Romantic-era fantasy, part esoteric invention akin to Indiana Jones-style archaeology. Entertaining? Certainly. Historically accurate? No.

Etteilla - Jean-Baptiste Alliette (1738-1791)

Above: according to Etteilla: "There are two kinds of knowledge: one comes from experience and wisdom, and the other is natural intuition. Intuition is greater than all other human knowledge, except for the simple and wise belief in one God."

The first pack specifically designed for cartomancy was created by Etteilla, engraved by Pierre-François Basan (1723-1797), published in 1788 as a hand-coloured tableau. This deck, a radical departure from the Tarot de Marseille, was steeped in imagined Egyptian symbolism. Three main versions followed:

- Grand Etteilla I (closest to the original, published by Pierre Mongie l’Aîné in 1826)

- Grand Etteilla II (Simon Blocquel, 1838)

- Grand Etteilla III (De La Rue, 1867)

These decks were about as authentically Egyptian as Disney’s Aladdin is authentically Arabic.

Above: Etteilla I Egyptian-inspired tarot, with faux-Egyptian symbols, published by Grimaud, Paris. Images courtesy of Adam West-Watson.

Etteilla further muddied the waters with a series of monographs (1788 onward) on cartomancy and the Egyptian Book of Thoth, which only deepened the superstitious confusion rather than clarifying his system.

Eliphas Lévi (8 February 1810 – 31 May 1875)

Éliphas Lévi, another influential 19th-century French occultist, reshaped Tarot’s esoteric legacy. In works like Transcendental Magic he connected the cards to the Kabbalah and Hebrew mysticism, framing them not as mere fortune-telling tools but as a symbolic map of cosmic and human mysteries. His theories became foundational for modern occult Tarot.

Papus (13 July 1865 – 25 October 1916)

Papus (Gérard Encausse) further developed these ideas in The Tarot of the Bohemians (1889), blending Kabbalistic, Hermetic, and Egyptian influences into a comprehensive divinatory system. His work cemented the Tarot’s place in Western esotericism.

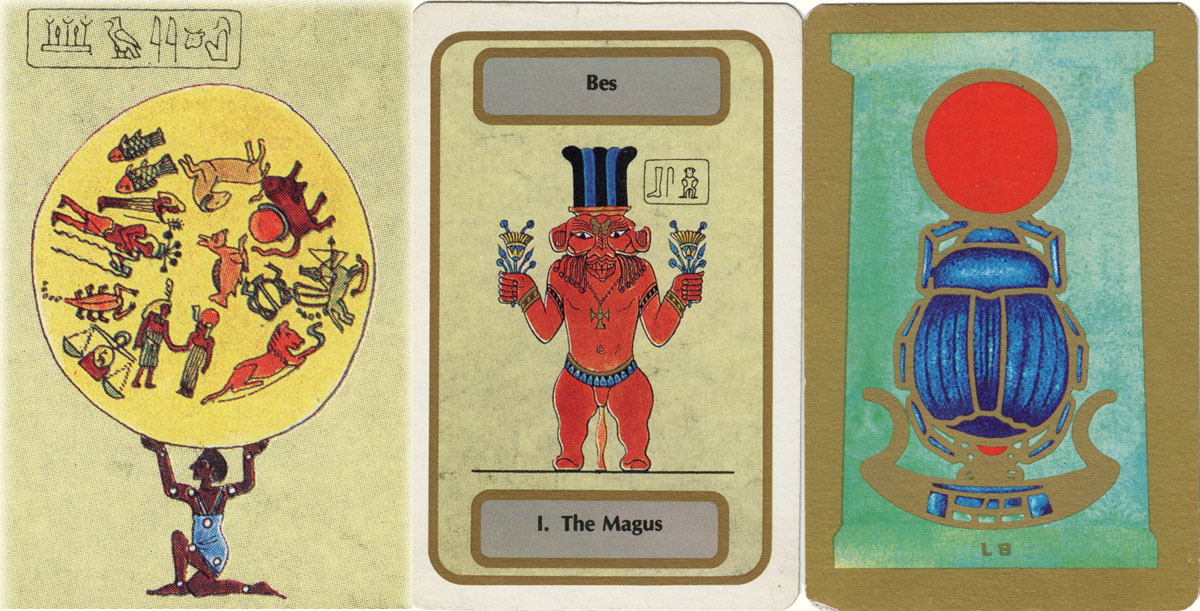

Below are two Latin-American Egyptian tarots which incorporate many new symbolic references mapped onto the cards:

Above: Egyptian-style tarot issued by Franco Mora Ruiz from Mexico, c.1975.

Above: fantasy Egyptian Tarot inspired by ancient Egyptian art, mythology and iconography, published by Naipes La Banca, Buenos Aires, c.1980.

See also: Ramses II Tarot from Peru. c.1975►

In summary: the "Egyptian Tarot" is a 19th-century Romantic and occult invention, stemming from Court de Gébelin’s theories and later expanded by figures like Etteilla, Lévi, and Papus. Studying it for ancient wisdom is like studying Indiana Jones for archaeology or Star Wars for astrophysics — fun, but not factual.

This fascination with "lost wisdom" arose alongside the Renaissance revival of classical studies, the Romantic era’s obsession with antiquities (Stonehenge, Druids, etc.), and later Occult Revivals and New Age spirituality. The Tarot, originally a 15th-century Italian card game, became a vessel for mystical, philosophical, and psychological ideas.

As René Descartes noted: “Nothing can be proved or disproved by unproved principles.” The rise of empirical science challenged symbolic mysticism, yet the Tarot endured, evolving into the diverse tradition we know today.

English occultists like Aleister Crowley and A.E. Waite developed new perspectives. Waite's tarot deck with artwork by Pamela Colman Smith includes illustrated numeral cards suitable for divination and this has become a template for many modern decks. "The tarot embodies symbolical presentations of universal ideas, behind which lie all the implicits of the human mind..." A.E. Waite, The Pictorial Key to the Tarot, 1910.

Multidisciplinary Approach

Above First Card: Judgement from the Thai Anatta Tarot showing a Buddha judging souls before they enter the afterlife.

Above Second Card: Page of Swords shown as a Thai Yak, or Giant Demons which play an important role within Thai mythology as well as Thai Buddhism.

Above Third Card: The Hierophant, sometimes refered to as the Pope, from the Siamese tarot, depicted as a Bodhisattva with 2 disciples.

Modern tarot decks now draw upon an extraordinarily wide range of traditions, including Western esotericism and alchemy, Buddhism, Sufism, Egyptian initiations, mystical Christianity, Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, Celtic mythology, Druidism, and many others, often suggesting a symbolic resonance with all of them at once. Almost any belief system or philosophy can now be mapped onto the tarot, allowing users to form an immediate affinity with the images, which become sources of meaning, reflection, or guidance.

Tarot has also achieved widespread popularity far beyond its original Western cultural context. In parts of East and Southeast Asia, for example, tarot is often approached in a relaxed and playful spirit. In Thailand, tarot imagery may incorporate animist beliefs alongside Buddhism, and the activity itself is frequently described as something one “plays,” much as one might “play Facebook.” This attitude reflects a broader contemporary shift toward tarot as a flexible cultural practice rather than a fixed symbolic system.

As a result, Tarot Studies now span a wide range of academic disciplines, including art history, literature, the humanities and cultural studies. Scholarly work ranges from historical investigation to interpretive and practical approaches to imagery and symbolism. Tarot has clearly become an eclectic and interdisciplinary field, shaped as much by reception and reuse as by historical origin.

Personal Mysticism and Spirituality

Much of tarot’s modern appeal lies in a desire to explore meaning, identity, and purpose without reliance on formal religious institutions. The cards offer a symbolic framework that can be adapted to almost any personal worldview. Through engagement with tarot imagery, individuals may gain new perspectives, articulate inner experiences, or construct private forms of spiritual understanding.

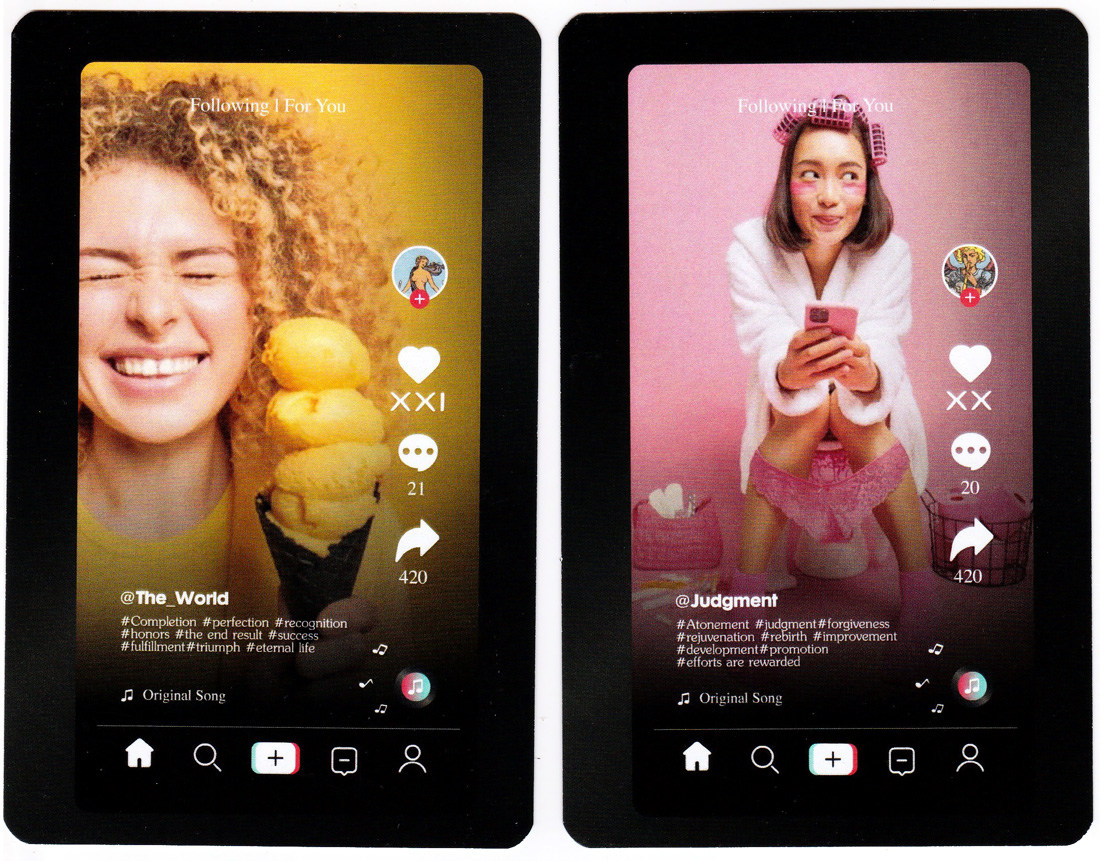

At the same time, tarot has become increasingly entwined with popular culture. A proliferation of decks based on video games, cinema, fantasy literature and branded franchises, such as Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones, Dungeons & Dragons, Disney and others have transformed tarot into a familiar and accessible cultural product. In many contexts, tarot reading now functions as entertainment or a social activity, and decks are often purchased as licensed merchandise rather than as tools of long-term symbolic study.

For younger audiences especially, such decks can feel more immediately legible than traditional iconography. Recognisable characters and narratives provide ready-made points of entry, reducing the interpretive distance that older symbolic systems require.

Above: TikTok Tarot created by Carmen Graf, is a unique tarot deck inspired by the Chinese video-sharing social network. more →

Above: Hip Hop Tarot designed by Ben Gore more →

Above: Branded Tarot Decks and Modern Mystic Lifestyle more →

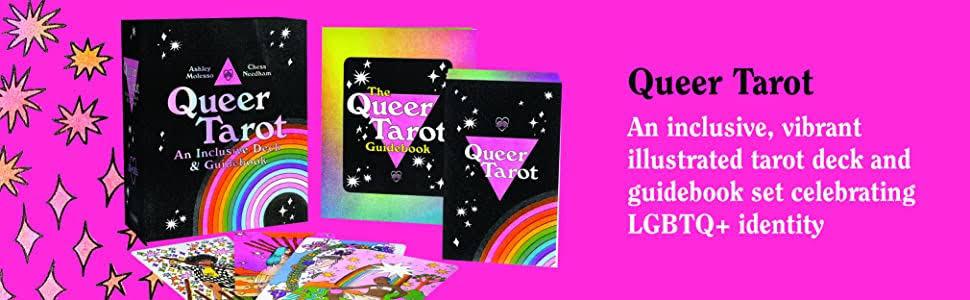

Identity and self-representation

From the mid-twentieth century onwards, identity politics emerged as a powerful force within social and cultural movements concerned with civil rights, gender equality, sexuality, disability, and cultural recognition. In parallel, tarot has been reimagined and adapted to reflect these evolving concerns. Decks now frequently foreground particular identities, experiences, or perspectives, allowing tarot to function as a medium of affirmation, representation, and self-expression. In this respect, modern tarot’s role in affirmation and self-expression echoes an earlier function of elite tarot packs, which likewise operated as symbolic statements of identity—though within very different social and cultural frameworks.

Above: sex is more complicated than 'just two'. Gender identity and expression is a psychosocial construct with a spectrum of valid expressions, hence the rainbow flag. Each individual is unique and can define what spirituality means to them personally, without necessarily any outside institutions defining it for you. In certain periods, alternative spiritual beliefs were considered heretical and had to remain concealed. Tarot became part of a counter-culture that operated underground. However, in today's context, we embrace multiculturalism, allowing individuals the freedom to believe and practice as they choose. This openness has led to an abundance of diverse Tarot decks, reflecting the myriad perspectives and preferences of its practitioners.

Many contemporary tarot packs can therefore be understood as compendia of lived experience, shaped by the artist’s personal, cultural, or spiritual outlook. Tarot has become both a vehicle for individual meaning-making and an expressive art form embedded within broader currents of Western esotericism and popular spirituality.

Yet this diversity of themes and identities often unfolds within a remarkably stable structural framework. While imagery, style and cultural reference have multiplied, the underlying symbolic grammar of many modern decks remains closely aligned with the Rider–Waite–Smith (RWS) model. In this sense, modern tarot reveals a tension between visual and ideological plurality on the one hand, and structural continuity on the other—a tension that invites closer reflection on originality, adaptation and the market forces shaping contemporary tarot production.

From Sola-Busca to Rider-Waite, and beyond

Seen in historical perspective, the development of tarot imagery reveals a clear sequence of transformation. The Sola-Busca tarot represents an early and largely isolated experiment: a learned, humanist deck that introduced fully illustrated numeral cards as moral and allegorical scenes, without establishing a fixed symbolic system or divinatory programme. Its imagery functioned within a narrow elite context and did not generate a lasting tradition. By contrast, the RWS deck of 1909 marked a decisive structural turning point. Drawing upon the precedent of illustrated pips encountered in the Sola-Busca, Waite translated scenic minor arcana into a coherent esoteric framework adapted to modern spiritual concerns, while Pamela Colman Smith gave this system a compelling and reproducible visual language. In the mid-twentieth century, the widespread publication and distribution of the RWS deck, most notably through Stuart R. Kaplan and U.S. Games Systems, consolidated this symbolic architecture as the normative model for tarot. Most subsequent decks, despite immense variation in theme, style, and cultural reference, have adopted this architecture with only superficial modification. The result is a paradox of modern tarot: an unprecedented diversity of imagery and identity, built upon a largely unchanged structural model first stabilised in the early twentieth century.

REFERENCES & RESOURCES

Anonymous, (translated by Robert Powell), Meditations on the Tarot, a Journey into Christian Hermeticism, Jeremy P. Tarcher, Penguin Group, USA, 2002. Copyright © 1985 by Martin Kriele. Online at Archive.com►

Benjamine, Elbert, (C. C, Zain) Astrological Signatures, Church of Light, 1925 & 2002. Chapter 1, The Two Keys►

de Gébelin, Antoine Court, Monde Primitif, analysé et comparé avec le monde moderne (vol.8), Paris, 1781.

Dummett, Michael: A Brief Sketch of the History of Tarot Cards, The Playing-card, Journal of the IPCS, vol.33 no.4, Apr-June 2005.

Dann, Kevin Etteilla's Livre de Thot Tarot (ca.1789), The Public Domain Review, Oct 2022.

Etteilla: Collection précieuse des tableaux de la Doctrine de Mercure dans laquelle se trouve le chemin royal de la vie humaine, 1788, BnF.

Farley, Helen: A Cultural History of Tarot, published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd.

Fontainelle, Earl: The Secret History of Western Esotericism►

Hunt, Ellie: When the mystical goes mainstream: how tarot became a self-care phenomenon►

Jodorowsky, Alejandro and Costa, Marianne: The Way of the Tarot, Destiny Books, 2009.

Keizer, Lewis: The Esoteric Origins of Tarot: more than a wicked pack of cards, included in The Underground Stream by Christine Payne Towler, Noreah Press, 1999. Can be found here►

Orsini, Julia; Lemarchand, Mlle; d'Odoucet, M. M.; Høgnesen, Marius (translator); The Grand Etteilla, self-published, 2021.

Penco, Carlo: Dummett and the Game of Tarot, Teorema, 2012

Poncet, Christophe: The Mysteries of the Tarot of Marseille, online: www.3x7.org►

Wintle, Prier: Attributes of the Egyptian Tarot: Attributes of the Egyptian Tarot►

Thanks to Samten de Wet for additional research and tarot material►

来源:https://www.wopc.co.uk/tarot/perspectives-on-the-history-of-tarot